Genome Structure and Functional Annotation: Methods and Databases

- Ceyda Güven

- Sep 19, 2025

- 7 min read

The genome is the fundamental structure underlying heredity in organisms. Genomic information serves as a kind of library about the organism. In addition to directing essential biological functions of cells such as growth, development, and metabolism, the genome also contains non-coding DNA regions, regulatory regions, and repetitive sequences. The definition of a genome is not limited to DNA alone. In some organisms, genetic material exists in the form of RNA for example, in RNA viruses. Genomic research provides highly significant insights across various fields of life sciences. One of the most frequently studied areas is evolutionary biology, which covers subjects such as the origins of species and the uncovering of phylogenetic relationships. These studies rely on observing the similarities and differences between genome sequences. Genome analyses also play a critical role in medical research on diseases. They contribute to identifying the causes of genetic disorders, shedding light on the molecular basis of complex diseases such as cancer, and developing personalized medicine.

Sequencing technologies enable the execution of genomic analyses and are constantly advancing. The concept of DNA sequencing was first introduced by Sanger, who developed a method in 1977 known as Sanger sequencing. Although this method laid the foundation of genome science, it was limited in scale. This limitation gave rise to Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies, which made it possible to sequence millions of DNA fragments simultaneously at high speed. Third-generation sequencing technologies, with their ability to generate long reads from single molecules, have further contributed to resolving complex genomic regions (1,2). The coding regions of DNA, called genes, are responsible for the synthesis of proteins or functional RNAs. Genes, which consist of exons and introns, are translated into amino acid sequences during translation to perform their functions. It is known that only about 2% of the human genome codes for proteins. The remaining 98% does not code but has critical biological roles. Non-coding regions include gene regulation, alternative splicing mechanisms, and intergenic regions. Regulatory regions, which include promoters, enhancers, and silencers, play a key role in controlling gene expression. These regulatory sequences within the genome shape the gene expression profiles of cells (3).

What is Functional Annotation?

Functional annotation is the process of predicting the biochemical functions and biological roles of potential genes obtained from genome sequences—that is, adding biological information to them. While structural annotation is limited to determining the locations of genes and their exon–intron organization, functional annotation seeks to explain the processes in which the proteins derived from these genes are involved. In bioinformatics analyses, functional annotation is the fundamental step for answering questions such as how genes contribute to biological processes and which pathways or networks they are part of (4).

Functional Annotation Approaches

To assign biological functions to genes, prediction algorithms based on similarity to known genes can be used. In addition, functional assignments can be made by performing homology searches of sequences against existing databases. Initially, sequence alignment tools are used to identify similarities with known genes. Tools such as BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) are commonly employed for this purpose. Moreover, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis allows categorizing and defining the roles of genes. This process is not limited to protein-coding genes; it can also be applied to non-coding regions such as microRNAs and ribosomal RNAs. Control regions like promoters, enhancers, and transcription factor binding sites also help us understand the roles of genes in cellular processes. One of the fundamental steps of functional annotation is the identification of non-coding regions. Non-coding sequences are separated, followed by the delineation of the boundaries of coding regions. Certain regulatory elements around the gene serve as guides during this stage. Once genes are identified, functional labels are assigned to them (5).

Sequence-Based Methods

There are numerous methods and tools used in functional annotation. The annotation step can be completed by employing different databases and tools. In sequence similarity–based approaches, tools such as BLAST and FASTA are commonly used. BLAST is the most widely applied tool, enabling the alignment of genes or protein sequences of interest with known sequences and predicting their functions based on similarity percentages. Similarly, FASTA is another algorithm that relies on sequence alignment (6).

Evolutionary Approaches

In evolutionary approaches, the examination of related genes serves as a powerful tool for function prediction. Ortholog–paralog analyses can provide guidance in the process of functional determination. Tools such as COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) or its eukaryote-specific version KOG (EuKaryotic Orthologous Groups) allow proteins to be grouped according to their evolutionary relatives for functional classification. COG enables the comprehensive functional characterization of bacterial and archaeal genes based on sequence similarities that reflect their evolutionary origins (6).

Ontology-Based Analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) is an international bioinformatics project that aims to describe the biological functions of genes and proteins using a standardized vocabulary and hierarchical structure. Widely used in functional annotation, the GO system classifies the biological roles of genes into three main categories: Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC). Biological Process (BP): Refers to the biological objectives achieved by a gene or gene product. It can also be described as the transformation of organized molecular structures into other structures through physical or chemical processes. This category includes both higher-level processes such as cell growth and signal transduction, as well as lower-level, more specific processes such as translation and pyrimidine metabolism. Molecular Function (MF): As the name suggests, this describes what a gene or gene complex does or is likely to do. It also covers the potential biochemical activities of a gene product, such as its ability to bind specific ligands or structures. Examples include functions like “enzyme,” “transporter,” and “receptor ligand.” Cellular Component (CC): Refers to the location within the cell where a gene product is active. This category includes terms such as ribosome, proteasome, Golgi apparatus, and nuclear membrane. The terms listed here primarily encompass eukaryotic cell structures (7).

Another widely used resource is KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes), a comprehensive knowledge base that integrates genomic sequences with high-level functional information. The GENES module contains up-to-date gene catalogs of all fully sequenced organisms as well as some partial genomes. The PATHWAY section provides graphical representations of fundamental biological processes such as metabolism, membrane transport, cell cycle, and signal transduction. These graphical maps are supported by ortholog group tables that reveal conserved pathway motifs, which facilitate gene function prediction. A third major component, the LIGAND database, provides detailed information about chemical compounds, enzymes, and the reaction networks connecting them. KEGG also offers Java-based interactive tools for browsing genome maps, comparing pathways across maps, and managing expression profiles, in addition to including sequence comparison and pathway computation algorithms. The databases are updated daily and are freely available to researchers (8).

Database Querying

In the process of genome annotation, databases play a central role in transforming raw sequences into meaningful information. Genomes obtained from sequencing technologies, on their own, do not convey meaning and cannot be interpreted directly. To make the data usable in a meaningful context, it must be compared against databases. In addition, standardization ensures that different researchers use a common terminology. Databases used in the annotation stage are critical for scientific validity and reproducibility. At this stage of analysis, core genome and transcriptome databases, annotation platforms, and protein-focused databases provide essential support to researchers. One of the most comprehensive and widely used databases is the Ensembl genome database project, which began in 1999 and continues today. Ensembl serves as a vast and complete genomic information source, offering gene sets, annotations of orthologous and paralogous genes, as well as extensive variation and regulatory data. With the BioMart tool provided by the resource, researchers can perform queries across large genomic datasets. The Ensembl interface appears as shown in Figure 1 (9).

The UCSC Genome Browser, introduced in 2002, is a widely used platform for genome annotation and visualization. Users can view exon–intron structures, regulatory regions, and variations within gene regions. They can also upload their own data and compare it with available reference genomes. The homepage of the website appears as shown in Figure 2. Usage guides can be accessed via the “See our new tutorials page!” button (11).

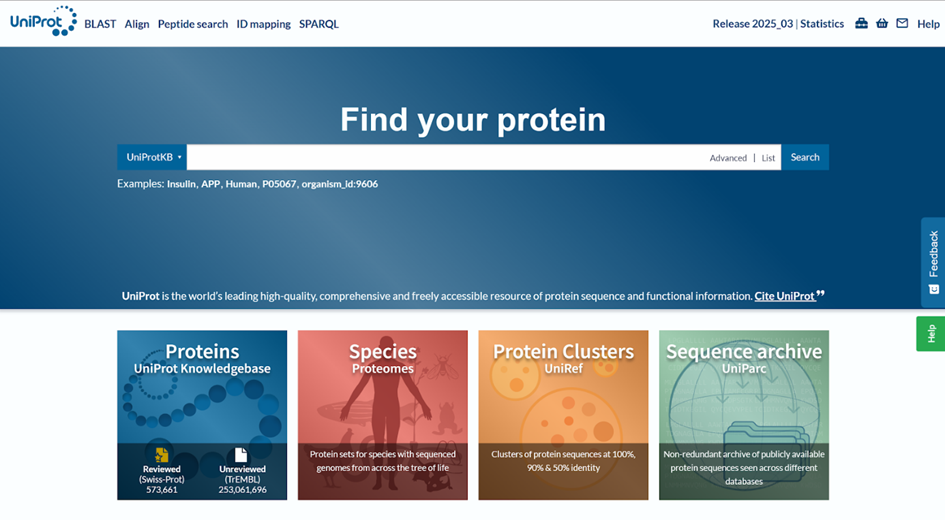

The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) is one of the most comprehensive and reliable databases for protein sequences and functional analysis. Officially announced in 2007, this resource was created by merging the Swiss-Prot, TrEMBL, and PIR-PSD databases. UniProt provides detailed information on protein sequences, structures, functions, cellular localizations, and interactions, while also establishing cross-links with other databases such as KEGG to facilitate researchers’ access to information. The UniProt interface is shown in Figure 3 (13).

Genome annotation is the process of biologically interpreting raw data obtained from sequencing technologies. In this process, the identification of coding and non-coding regions, the determination of gene functions, and their placement within biological networks are of critical importance. Databases such as Ensembl, UCSC Genome Browser, UniProt, and KEGG provide comprehensive support to researchers in the functional interpretation of genomes.

In conclusion, genome annotation is indispensable for both basic research and clinical or industrial applications. It paves the way for scientific advancements in numerous areas, from understanding diseases and identifying new therapeutic targets to driving progress in biotechnology and improving agricultural productivity.

References

1) Metzker, M. L. (2010). Sequencing technologies — the next generation. Nature Reviews Genetics, 11(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2626

2) Pareek, C. S., Smoczynski, R., & Tretyn, A. (2011). Sequencing technologies and genome sequencing. Journal of Applied Genetics, 52(4), 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13353-011-0057-x

3) Monti, R., & Ohler, U. (2023). Toward identification of functional sequences and variants in noncoding DNA. Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science, 6(1), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biodatasci-122120-110102

4) Aubourg, S., & Rouzé, P. (2001). Genome annotation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 39(3–4), 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0981-9428(01)01242-6

5) Hashmi, H. (2022). Functional annotation of genomes: A comprehensive review. In S. Singh & R. K. Dwivedi (Eds.), Bioinformatics computing (pp. 84–89).

6) Galperin, M. Y., Vera Alvarez, R., Karamycheva, S., Makarova, K. S., Wolf, Y. I., Landsman, D., & Koonin, E. V. (2025). COG database update 2024. Nucleic acids research, 53(D1), D356–D363. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae983

7) Ashburner, M. et al. (2000). Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics 25, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556

8) Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. (2000) KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 28(1):27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27

9) Flicek, P. et al. (2009) Ensembl's 10th year, Nucleic Acids Research, Volume 38, Issue suppl_1, 1 January 2010, Pages D557–D562, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp972

11) Kent, W. J., Sugnet, C. W., Furey, T. S., Roskin, K. M., Pringle, T. H., Zahler, A. M., & Haussler, D. (2002). The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome research, 12(6), 996–1006. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.229102

13) UniProt Consortium. (2007). The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt). Nucleic Acids Research, 35(suppl_1), D193–D197. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl929

Comments